- You are here:

- Home »

- Top Story »

- Nifty finance or indentured servitude? Taking slices of graduates’ future income

Nifty finance or indentured servitude? Taking slices of graduates’ future income

Yield-starved investors are taking slices of graduates’ future income

Cassandra Este

Media Coordinator

The Posse List

13 November 2019 (Washington, DC) – Combine a crisis in college affordability with yield-starved investors and you get one of the more unusual financial products of the past decade: shares in students.

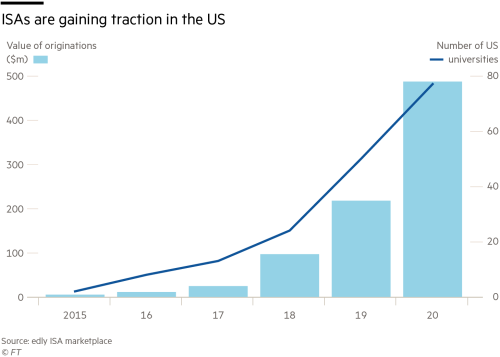

Income share agreements are an alternative to student loans that are gaining ground in the US. From only a handful several years ago, this academic year almost 50 American universities and technical academies offer them. Next year, about 100 will.

A student funding their education with an ISA gets money upfront in exchange for offering a share of their income after graduation — ranging from nothing if they are unemployed or on a low salary to potentially several multiples of what they received. Graduates continue paying a slice of their income until the ISA expires, usually after about a decade, or when they hit a repayment cap. Risk, in short, is shifted from borrower to lender. Said Charles Trafton, president of Edly, a recently-launched marketplace in New York that connects investors with ISA programmes:

“They might go backpacking for eight years and not pay you a dime, they’d be well within their rights”.

ISAs are not a new idea — Yale briefly offered one in the 1970s — but today a group of universities, investors, and start-ups claim they have managed to make ISAs work. If they are right, ISAs could be part of the answer to the mounting US student debt burden, sitting at more than $1.5tn, that has become a central issue for those competing for the Democratic presidential nomination.

ISAs are also attracting rare bipartisan interest in Washington. A bill being considered in Congress to give ISAs a regulatory framework has been co-sponsored by the Republican senator Marco Rubio and Christopher Coons, a Democrat. Nonetheless, proponents of widespread debt forgiveness such as Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders are wary.

Yet for now ISAs remain a niche product with much to prove; they compete in the $10bn-a-year private debt marketplace, rather than with $100bn-a-year government-subsidised loans. Borrowing from a bank or the government is still the dominant way to fund higher education in the US. But they are growing. A chart from a Financial Times article:

The most common way to administer an ISA is through a university or technical school, which will usually determine eligibility and co-invest alongside external investors. Some companies, though, offer direct-to-consumer ISAs, where students apply for the money directly.

But a university-administered ISA also appears to align the incentives of universities and students. The better that universities prepare students for the workforce, the greater the returns they will reap from their ISA programmes. ISAs have become particularly popular at institutions that offer crash courses in professionally-oriented skills such as coding or welding.

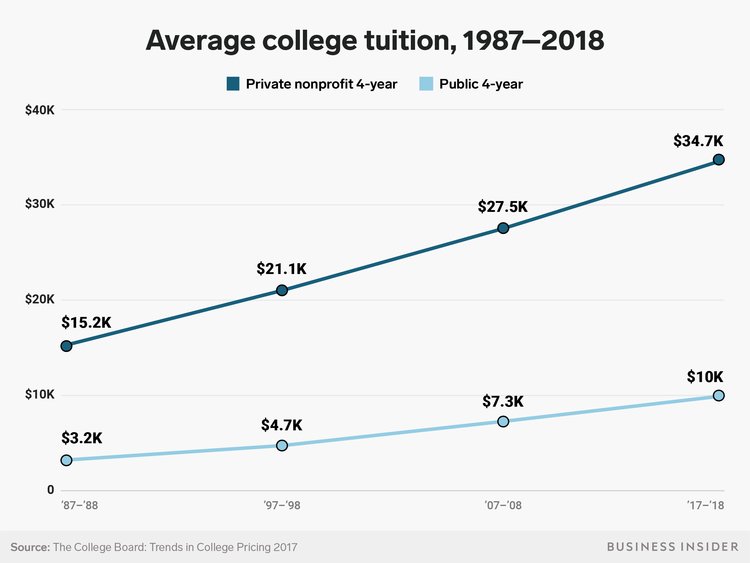

As major government bond markets offer negligible returns, the ground is certainly fertile for products that promise much more. ISAs for undergraduate degrees offer investors yields in the high single digits, said Mr Trafton, while those for technical schools offer yields in the low double digits. Tuition costs are enormous:

The tiny size of the market is a key impediment for major institutional investors. So far, only a handful of smaller investors have taken the plunge.

And anyone entering the market faces major risks. There is no case law on ISA defaults, nor bespoke regulation — although legislation currently in Congress may change that. Many institutions issuing them are only a few years old.

Marketing ISAs directly to students, without university involvement, is a more scalable but also more challenging model. How do you even underwrite 3,000 students from 3,000 different schools from 3,000 different majors? It’s a credit card portfolio of “twenty-somethings”. Higher education is the only place you would counsel someone you love to borrow 10 to 20 times their net worth and make a single investment (a university degree) with it and hope it works.

It is growing in Europe, too. ISAs are very prevalent in Germany, and those involved hope to export their expertise to the US.

However, many remain doubtful that ISAs are viable at all at a large scale. Many people view ISAs as indentured servitude. Investors believed that if you chose an ISA over debt, it meant your confidence in your future ability to earn was low.

And many have suggested less radical shifts to accomplish similar goals:

- mandating that universities cover some student defaults

- making employer student debt contributions tax-free

- increasing transparency on graduate incomes

In a sign of the financial challenges in American higher education, ISAs are by no means the most unconventional product available to universities. Pending final regulatory approval, Illinois universities will soon be able to purchase, for several thousand dollars per student, “American Dream Insurance”: a five-year student income guarantee.

If a student fails to earn above an income threshold — determined by the university they attend and the field they study — then Education Insurance Corporation, the start-up selling the insurance, will pay them the difference five years after they graduate.